Pharoah ride, Dutchess County Fair

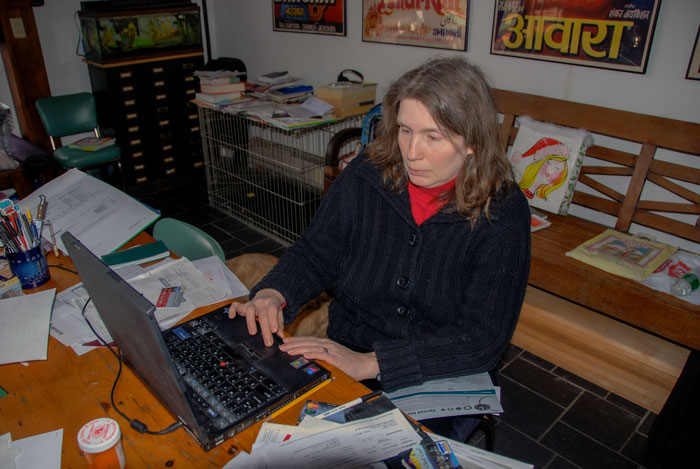

First photo with the Nikon: C at work

None of these pictures are very good, but I find them an interesting record of my first contact with a life-changing technology. When I got my first good film camera, a Honeywell-Pentax with three prime lenses, my life changed. When I got a four-track Tascam reel-to-reel audio recorder my life changed. When I got a Portapack video deck and camera my life changed. Likewise and to an even greater extent, my life changed when I got a Mac IIcx.

In 2006 the tech was a Nikon D80 DLSR with an 18-200mm lens. We were going to India a few weeks into 2007 and I was determined to have a good digital camera along for the ride. I'd shot my last roll of film in June of 2005; increasingly everything I captured had to be scanned and digitized. I was no longer shooting for print formats; now everything was going into an email or was posted online. Initially my digital imaging used camcorders of one kind or another; they all had methods of recording individual frames. The quality wasn’t good—there just weren’t enough pixels.

I can see from these first images with the Nikon that I didn’t know much about operating the camera. For one thing each image uses the built-in flash; after the first couple of weeks with the camera I’m not sure I ever used it again. Maybe it was all those years using Tri-X; available light is the only way I know how to shoot. There’s so much beauty in the photons falling as they will, beauty that I don’t know how to recreate with artificial lighting. I’m not saying that it can’t be done (look at the glamour photography of George Hurrell, for instance) but not by me.

There's no question that film has a look that cannot be duplicated in digital formats. For one thing, there's hell of lot more data in a frame of film. The average frame of 35mm film has about one-hundred megabits worth of “information.” Even shooting raw in a camera like the Nikon my average frame is twenty-eight to thirty megabits. Film is denser; it can be manipulated with more freedom even after it is digitized. In audio you'd say it has more dynamic range.

There's also no question that raw image capture on a big sensor—with little to no compression—really kicks ass. The actual process of getting the shot in modern cameras is so much easier: auto focus, auto aperture, auto shutter speed. When I first started shooting film I had a Japanese Leica knock-off with a misaligned viewfinder; I used an antique handheld light meter to make my exposures. Not until a week or two later would I find out what I'd shot; often disappointment was acute. It was so easy to ruin the shot. With digital the number of tech failures plummeted.

As a digital shooter I also had the advantage of almost unlimited storage capacity. Where I'd previously clicked the shutter thirty-six times, now I was clicking it five-hundred times. On my month-long honeymoon my suitcase held about thirty rolls of unexposed film; even when fascinated by what I was seeing I could rarely afford more than a couple shots. Shortly after the switch to the Nikon I remember returning home from a long weekend with a thousand exposures. It was no longer an expenditure to shoot as many images as I wanted. I became a curator of many happy accidents.