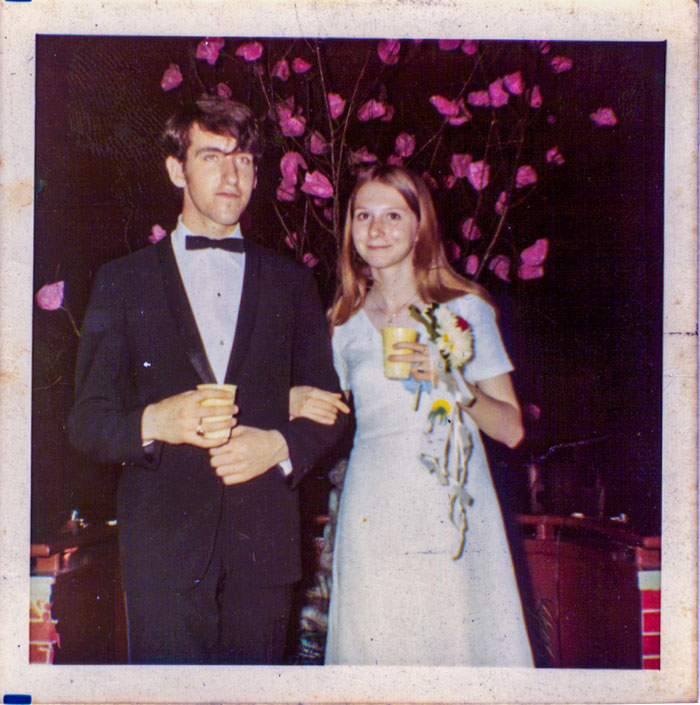

With Kathy at Graceland Mall

Before the winter was over in 1970 my grand affair with Kay came to an end. I loved her desperately, but began to realize—at the same time she was beginning to realize—that she hadn’t the same feelings for me. One night while walking down a sidewalk with her previous beaux Blake I saw how she let me fall behind while she stuck by his side. It made me realize how much more important Blake was to her than me. He was a good-looking guy, the son of Ohio State professors, and the product of a bohemian intellectual environment I could only envy from a distance. He was impossibly cool and I felt I couldn’t compete.

Kay was also the child of a university professor. She was surprised and appalled by the racial panic—Blake was black—in the extreme reaction of her father when her parents found her diary. Her father nailed shut the bedroom windows. She’d been climbing out of them for months then somehow making her way down to OSU. Blake lived in one of the old three-story houses provided for long-time faculty there, in an attic room on the top floor. She climbed up the outside of the house in the dark to join him. She pursued her love with the same intensity she brought to everything. I thought she was so courageous!

I think the suddenness of the ending made her relationship to Blake even more important to her. She attempted suicide by impulsively swallowing the contents of a bottle of aspirin. Her parents were relieved when I appeared: I’d take her mind off him, I was white, cautious, safe. But I was also a way for her to see him again; we spent a lot of time on campus in those days.

After weeks of agony in my basement bedroom—more tears were to follow—I called her and told her that I couldn’t continue. I couldn’t handle being in second place. She was surprised, I remember, but didn’t plead, didn’t try to hold on, which had the effect of confirming my suspicions.

At the time of the call I didn’t know that there was yet another guy in her life. He was an archetypal 60s bad boy who called himself Tink; he appeared on a motorcycle like someone from a Shangri-las tune. It was set up by a girlfriend of Kay’s who was playing matchmaker; maybe she thought I wasn’t exciting enough for someone so extraordinary. I didn’t find out about him till weeks after we’d broken up. They stayed together for years until he died, beheaded in a motorcycle accident. Kay died of a stroke a year or two later; I’m sure booze and drugs helped to bring that on. Kathy told me that Kay would call her, drunk, from the house trailer where she was living.

I’d never be quite so tragically in love again. Something about being sixteen made it all so intense.

I had stopped going out with Kathy the moment Kay gave me her telephone number; it’s a weak defense but I was swept off my feet. Kathy was a pragmatist, however, and began dating one of my best friends. His mother was opposed and found many ways of making his life difficult. Finally he gave in and broke it off with Kathy; it was the only way to get things back to normal.

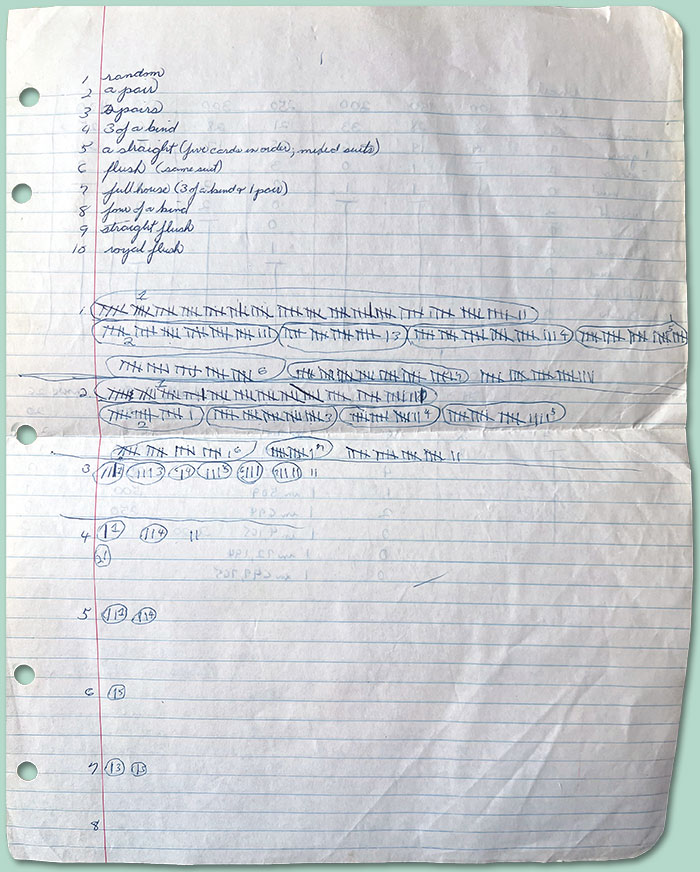

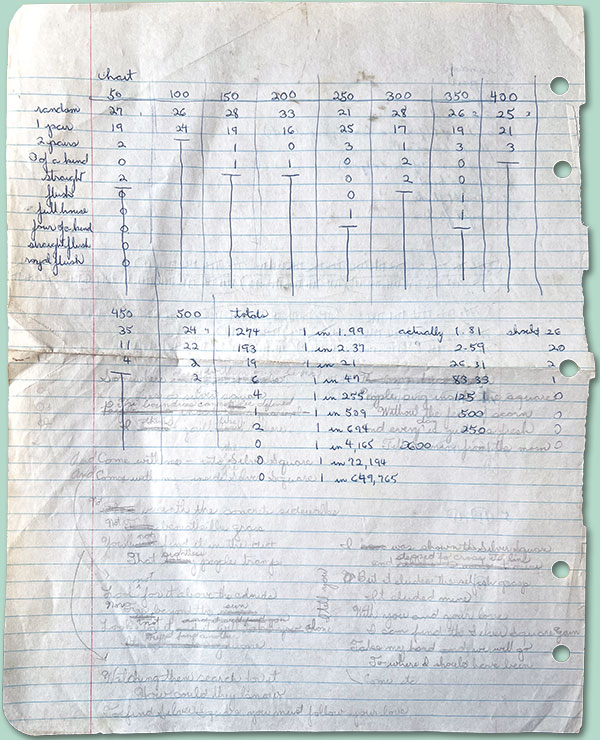

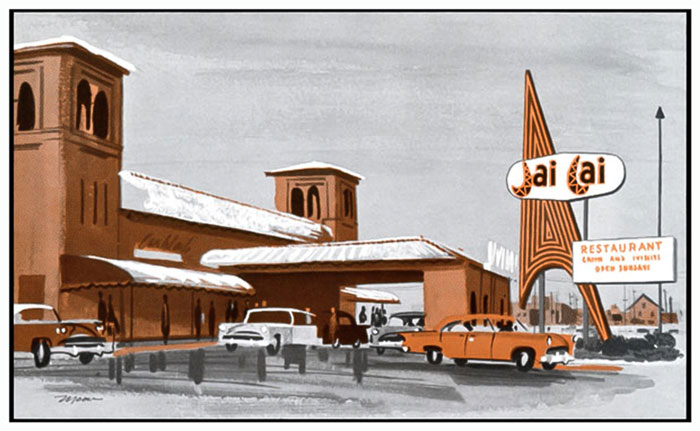

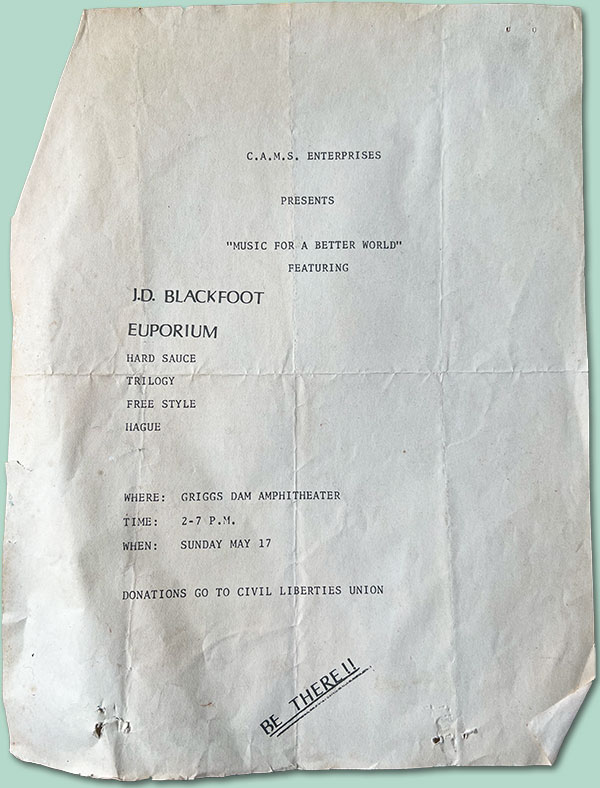

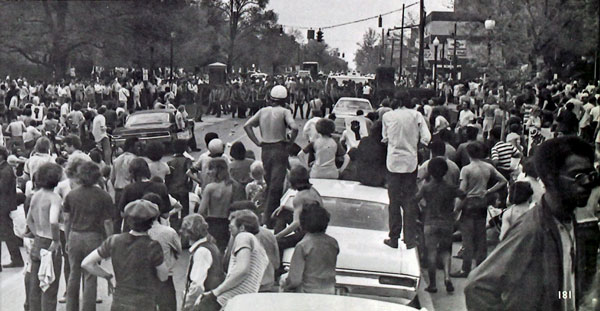

He worked in a laundromat at the Graceland shopping center and sometimes Kathy and I would stop by. I would cruise for 45s at Woolco while the two of them hung out at the laundry. I was there the day he ended things with her, the day the pictures included in this item were taken. And so Kathy found herself without a relationship at nearly the same moment I broke up with Kay.

We consoled each other but Kathy’s mom had issues with me. I couldn’t figure out why she didn’t like me; I was polite and certainly looked the part of a good boy. Dad had fled the chaos mom caused at some point; I met him a few times and Kathy was still close to him. After the divorce mom had to work as a cocktail waitress; maybe all this had an effect on her opinion about men. She was under intense financial pressure; the family was poor and lived in a rental in a tougher part of the West Side. Kathy’s beloved older brother, the only son, died in Vietnam just a year or two before I met her.

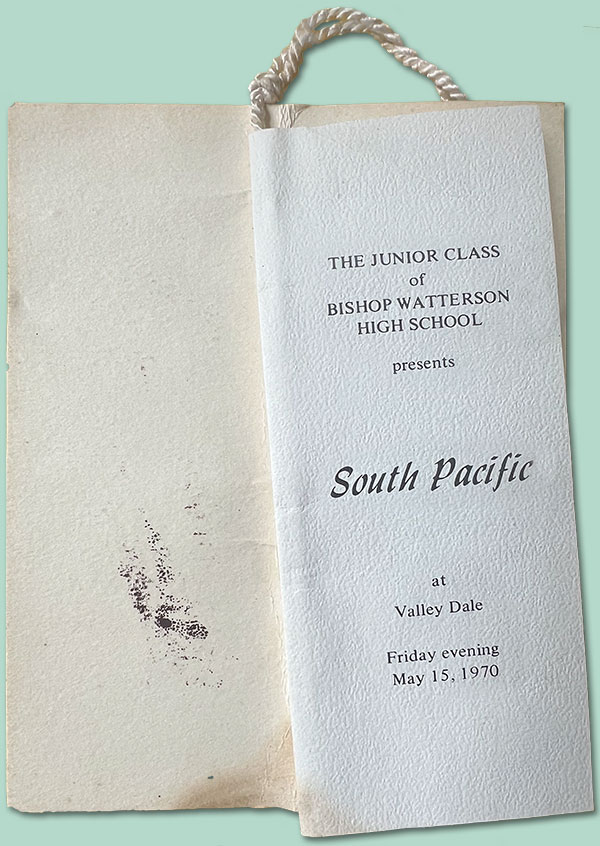

Later in the year I asked Kathy to go with me to the Junior Prom. She made her own dress and we talked about the evening for weeks. Then one might Mom said the prom wasn’t happening. Kathy told her she was going anyway. After she left with me her mother reacted by putting all of Kathy’s stuff in a pile on the floor and setting it on fire.

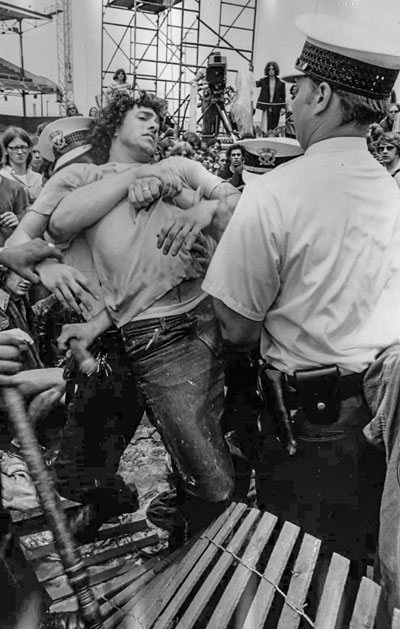

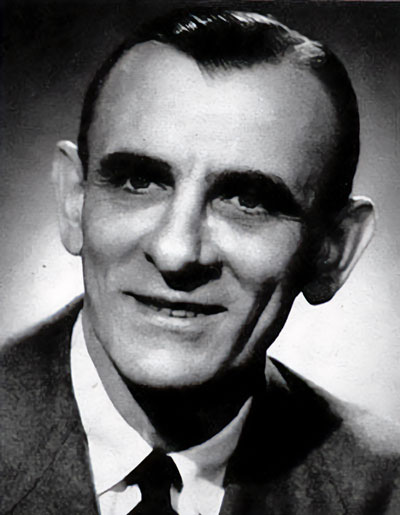

Sensenbrenner was an archetypal politico, a real-life version of an actor from Preston Sturges' repertory group in The Great McGinty. I remember him visiting my high school during a pep rally; I thought he looked like Lon Chaney Sr. He was an extremely popular maverick Democrat and a conservative mayor (every politician was a conservative in

1970 Ohio). My dad was a skilled GOP campaign manager; he was asked to

Sensenbrenner was an archetypal politico, a real-life version of an actor from Preston Sturges' repertory group in The Great McGinty. I remember him visiting my high school during a pep rally; I thought he looked like Lon Chaney Sr. He was an extremely popular maverick Democrat and a conservative mayor (every politician was a conservative in

1970 Ohio). My dad was a skilled GOP campaign manager; he was asked to