Joanne, another West High friend

She seemed like such a hippie to me and I admired her; Carla did not (this made more sense to me after the breakup). Hippies were so exotic to this fifteen-year-old boy: the style, the music, the pot, the ethos. The cultural shift was such a break from the suffocating fifties and too new to show any cracks. Like other post-pubescent boys of this period, I was also acutely aware of the change in sexual ideation from Donna Reed to Julie Christie.

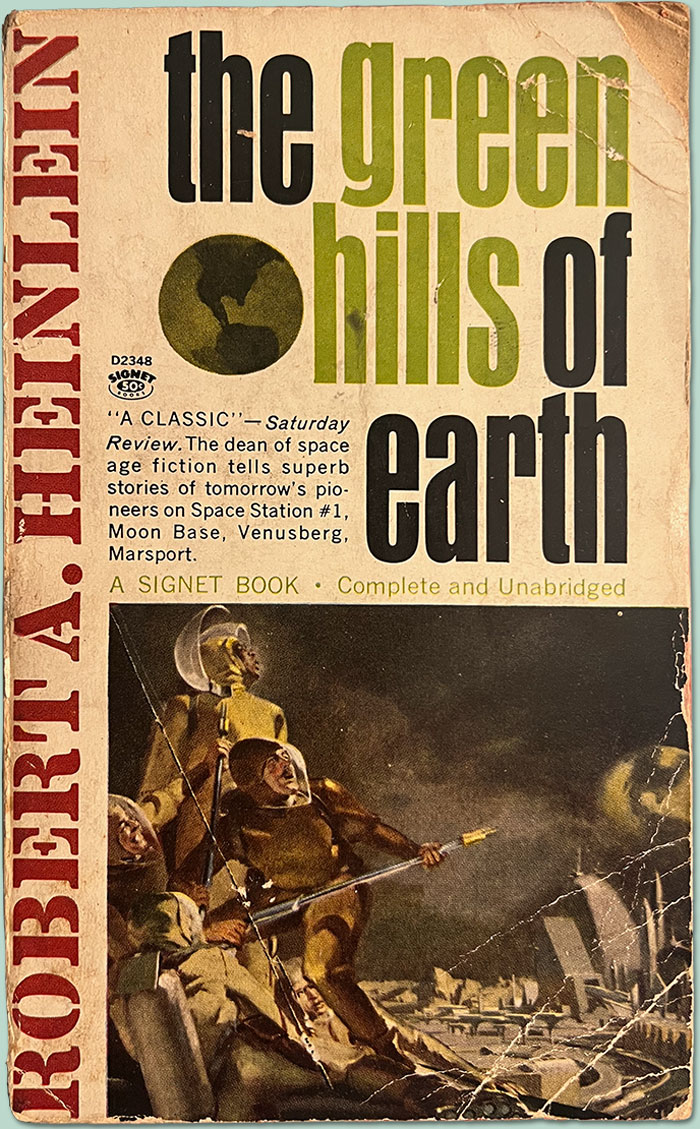

The Green Hills of Earth

One of the first books I’d ever read was a collection of Edgar Allan Poe. These collections were common in many households through the first half of the twentieth century; my father-in-law had his collection, too, along with his Hardy

Boys novels. After stories like The Strange Case of M. Valdemar

and Into the Maelstrom

it wasn’t much of a jump for me to science-fiction. I read the entire shelf devoted to the genre at the Linden branch library before I moved in ’65;

after the move I read the shelf at the Beechwold branch, then began to take the bus downtown to ransack the Central branch.

My brother and I used to attend the seventy-five-cent matinees at the Southern Theatre, a compact and elegant downtown theater that was beginning to fall on hard times. There were always three movies, usually a Hammer shocker, an exploitation flick from American International, and finally a Toho kaiju which we unsophisticates called a Godzilla movie. One day walking up to the High Street bus I found a used bookstore and entered Aladdin’s cave.

There were huge flat tables everywhere filled with paperback books. They were so cheap—probably a quarter—that I could buy them by the armful. Usually the front cover had been torn off, which meant the book had been returned to the publisher from the bookstore. I didn’t realize that till years later. They were supposed to be pulped by the publisher but they often found their way into these semi-legal discount shops instead.

That’s when I discovered the foundational authors of fifties and sixties sci-fi: Asimov, Clark, and Heinlein. There were many others, of course, and I read them all, but I kept coming back to these three. And there was no question as to my favorite: Robert Heinlein. Once I described to my shrink the books I read to escape my miserable youth; when I began to talk about Heinlein I wept, the only time in thirteen years of talk therapy that I cried.

A movie that changed movies

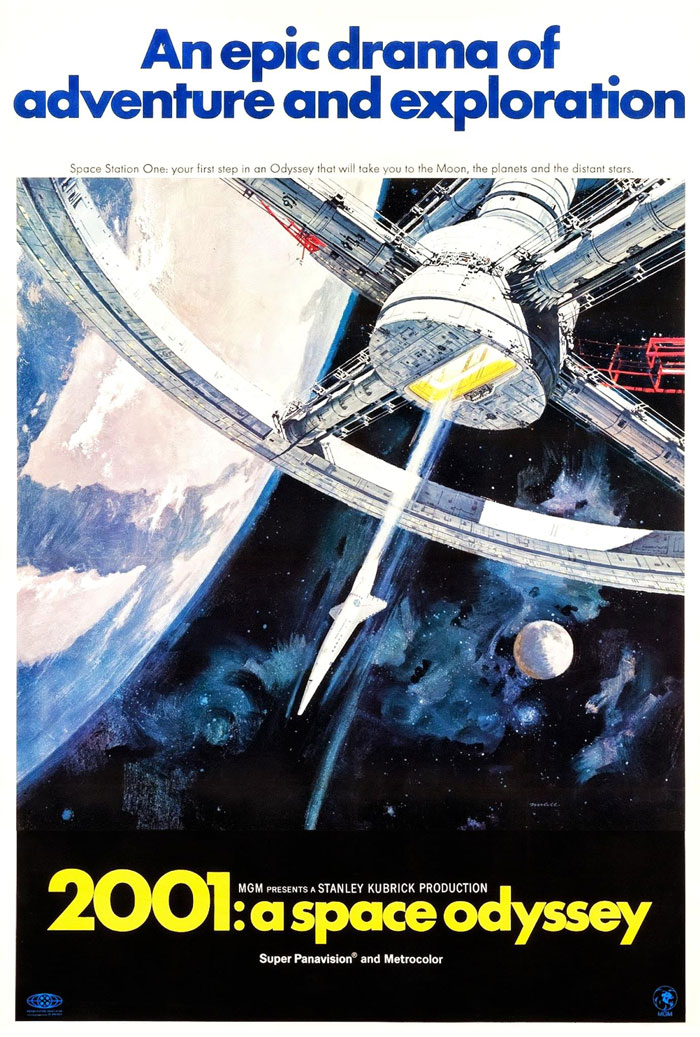

2001: A Space Odyssey opened December 6, 1968, at the RKO Grand, one of the few Cinerama theaters in central Ohio. It played for twenty-seven weeks. I went back several times; I felt as though I had waited for this film my entire life. I took my very first date to 2001, a girl named Robin who like me was a volunteer at a downtown museum called The Center of Science and Industry. She had the planetarium assignment and we all envied her.

The film played as a roadshow like The Sound of Music had done three years before: opening music behind a huge red curtain, an intermission, a program, reserved seats. While you found that reserved seat you were listening to

Ligeti’s Atmospheres,

one of the many chilling and perfectly chosen twentieth-century pieces that set a cool and cerebral tone and prepared you for something new.

And that music was playing over a perfectly calibrated six-track system! Most theaters in 1968 had a single Voice of the Theater speaker sitting dead center behind the screen; almost all soundtracks were mono as they had been since 1927 and the days of Vitaphone. 2001 was a profound experience for both ears and eyes.

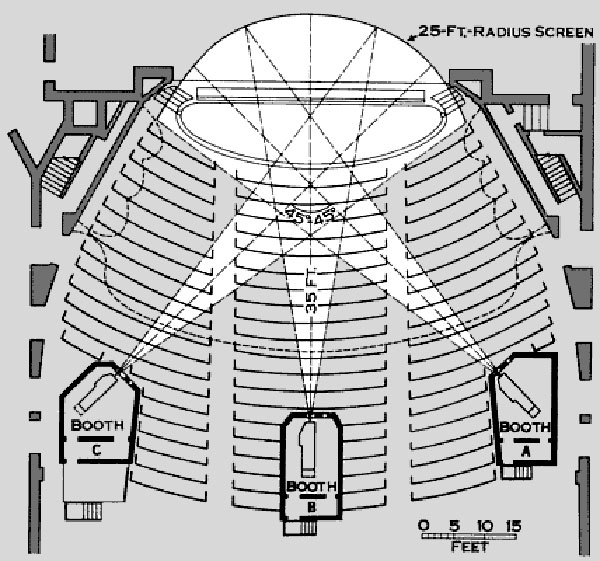

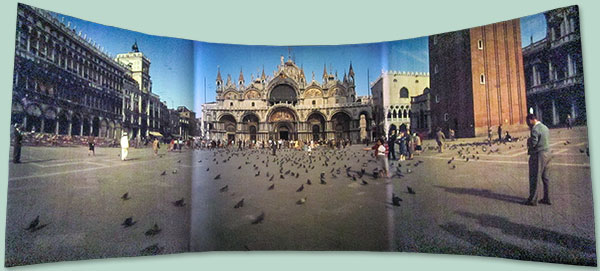

The screen at the RKO Grand was a giant curved cyclorama originally designed for the three-projector Cinerama system. Cinerama was the first commercially successful wide-screen format, introduced in 1952, and paved the way for Cinemascope and other formats later in the decade. It was an instant success even though its three-projector format was expensive to install. At the Grand the 75-foot curved screen reduced seating from 1150 to 860; higher ticket prices and packed screenings that ran for months made up the difference for the theatre owner.

Cinerama made millions despite its technical drawbacks. The size made anything a spectacle and did what all widescreen formats were supposed to do: get the audience away from crude early televisions and back downtown to the movies. None of the early Cinerama pictures had a plot. They were essentially travelogues and still brought in the crowds.

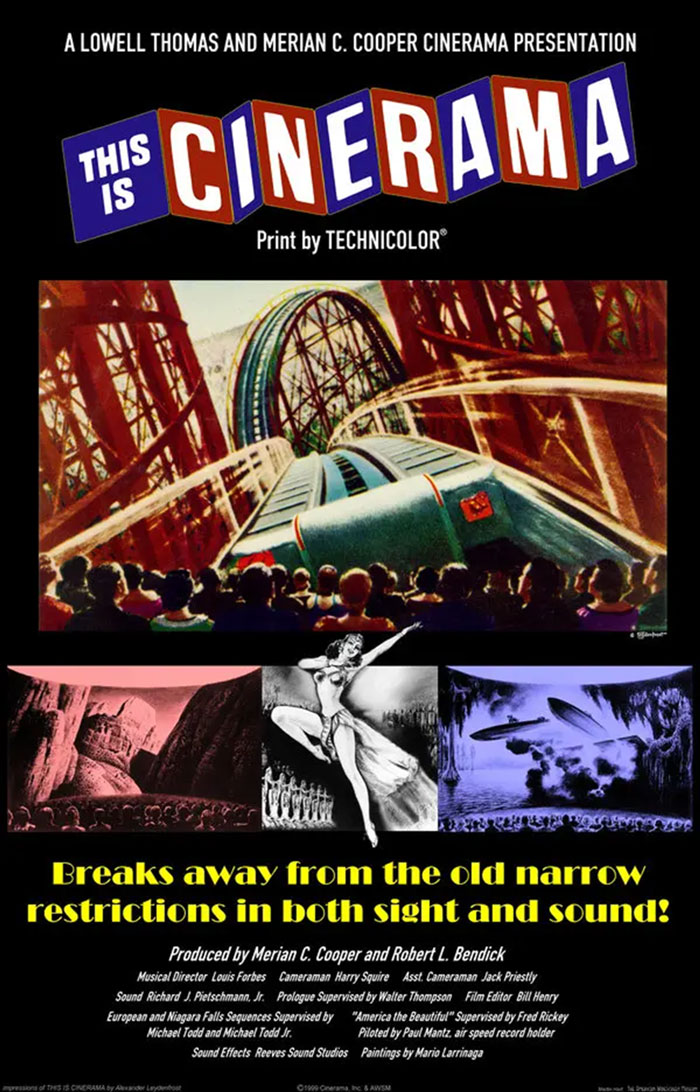

Note the name of Merian C. Cooper on the poster, a fascinating guy inextricably bound up

in Hollywood history. In 1927 he made a silent documentary called Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness that featured an elephant stampede sequence in Magnascope, one of the first ever widescreen presentations. In 1933 he was the

producer and co-director of King Kong. In the 1950s he went into business with his friend John Ford where he produced, among other notable films, The Searchers. This Is Cinerama was his last movie.

Note the name of Merian C. Cooper on the poster, a fascinating guy inextricably bound up

in Hollywood history. In 1927 he made a silent documentary called Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness that featured an elephant stampede sequence in Magnascope, one of the first ever widescreen presentations. In 1933 he was the

producer and co-director of King Kong. In the 1950s he went into business with his friend John Ford where he produced, among other notable films, The Searchers. This Is Cinerama was his last movie.

By the time 2001 appeared, improved lenses and formats like 70mm Ultra Panavison had pushed Cinerama off world screens. It had always been expensive: three cameras using three times as much film; three projectors running three times as many prints; new screens that had to be curved to maintain focus; and the new speakers neccessary to accomodate multiple audio tracks. And there was a flaw in the projected image, a flaw that was easily discernible to the audience: a blurred border between each of the three aligned images.

Ultra Panavision could do it all with one camera and the two usual projectors. The screen image was impeccable, the best wide-screen format ever devised, and it still had room on the prints for multi-channel stereo. 2001 was shot and projected in Ultra Panavison and even though it was shown in Cinerama theatres they had all been modified for 70mm by 1968.