Architectural rendering of the Indianola circa 1938

The Indianola Theater opened in 1938 with Stage Door, a Katherine Hepburn-Ginger Rogers starrer released the year before. Distribution patterns of that era typically opened A-list films in downtown movie palaces owned by the studios. The same three-hundred or so prints in the initial run would play the downtowns and then move out to suburban second-run houses (like the Indianola). After that the prints would hit the drive-ins and rural theaters (see The Last Picture Show.)

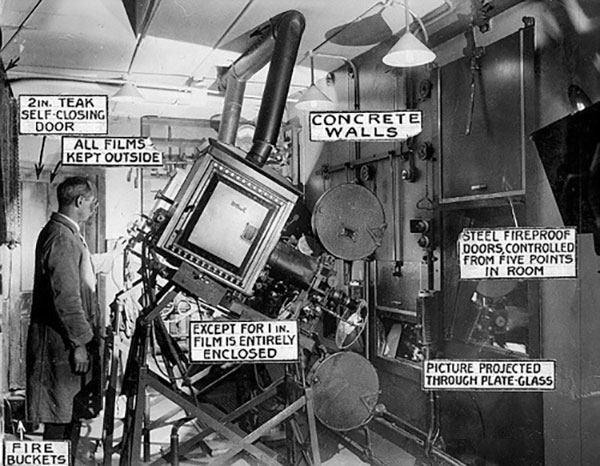

Initially studios regarded these prints as disposable, a staggering injustice to later audiences. We can understand: nitrocellulose film stocks were very difficult to store—they had a tendency to spontaneously burst into flames. This same nitrate stock was still in use in 1952; it was replaced that year by acetate "safety" film. A substantial part of the licensing test for new projectionists—and all projectionists needed a license, unlike many other theatrical niches—involved fire safety; the projectionist's booth was a study in safety procedures.

It was a solitary life in that projection booth. A quiet workplace could suddenly erupt into a

high-pressure and very public crisis. Worry number one: the carbon rods. An electrical arc between two rods provided the projector's light. They had to be adjusted or replaced fairly often. Maintaining the arc depended on keeping the rods

a precise distance from each other as the carbon burned down. The only way to check conditions was through a welder's glass embedded in the side of the light chamber. Theatrical exhibition then and now has low profit margins and suburban

exhibitors like the Indianola made every penny count; the projectionist was expected to burn every rod down to the filter, as it were.

It was a solitary life in that projection booth. A quiet workplace could suddenly erupt into a

high-pressure and very public crisis. Worry number one: the carbon rods. An electrical arc between two rods provided the projector's light. They had to be adjusted or replaced fairly often. Maintaining the arc depended on keeping the rods

a precise distance from each other as the carbon burned down. The only way to check conditions was through a welder's glass embedded in the side of the light chamber. Theatrical exhibition then and now has low profit margins and suburban

exhibitors like the Indianola made every penny count; the projectionist was expected to burn every rod down to the filter, as it were.

Worry number two was the changeover, the moment when everything had to be shifted to the second projector. Changeovers happened at the end of the reel, about every twenty minutes. The operator waited for cue marks to appear on the upper right corner of the screen (first cue); eight seconds later another dot would appear (the second cue) and a lever was thrown. The dots were not always in the same place or the same shape; each print had been marked individually as a last step before exhibition.

I learned all this stuff by working from 1969 to 1971 at Studio 35, the post-1964 incarnation of the Indianola. At one point I trained to be a projectionist. Tony, the scarfaced, pompadoured, and aviator-shaded guy who was teaching me thought I was a threat to his job. There was a lot of subtle resistance and the training never resulted in booth hours. I found operating the two projectors made me very tense; I think I was relieved when the training initiative collapsed and I returned to the candy counter downstairs.