Jeopardy day, Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood

years

years

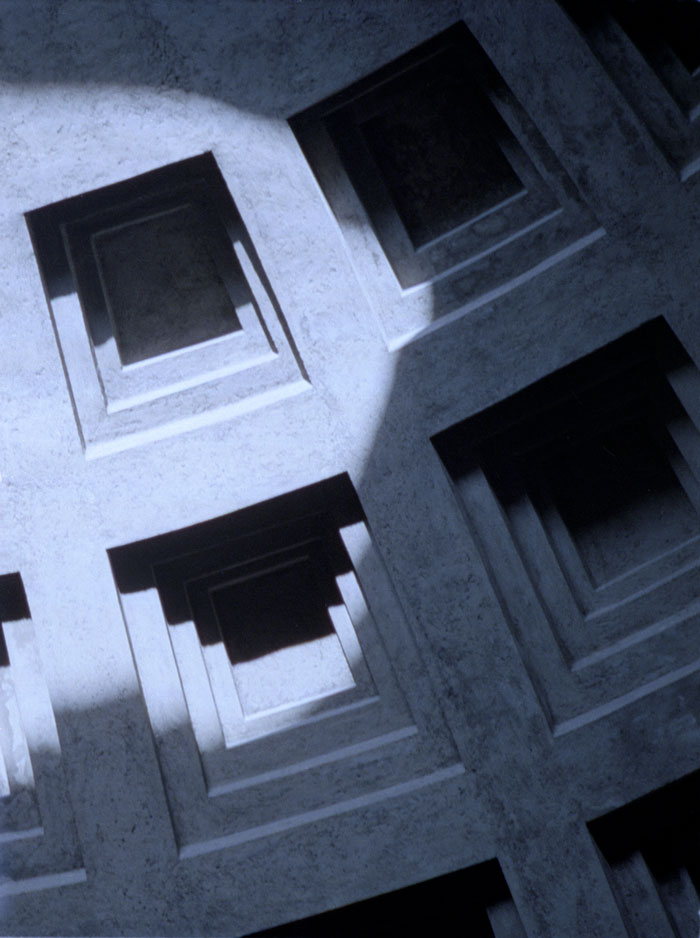

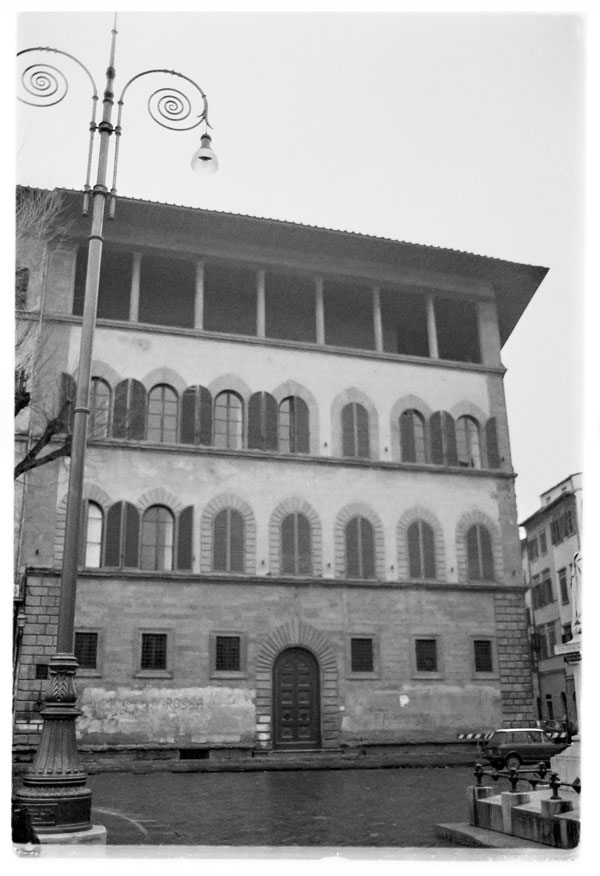

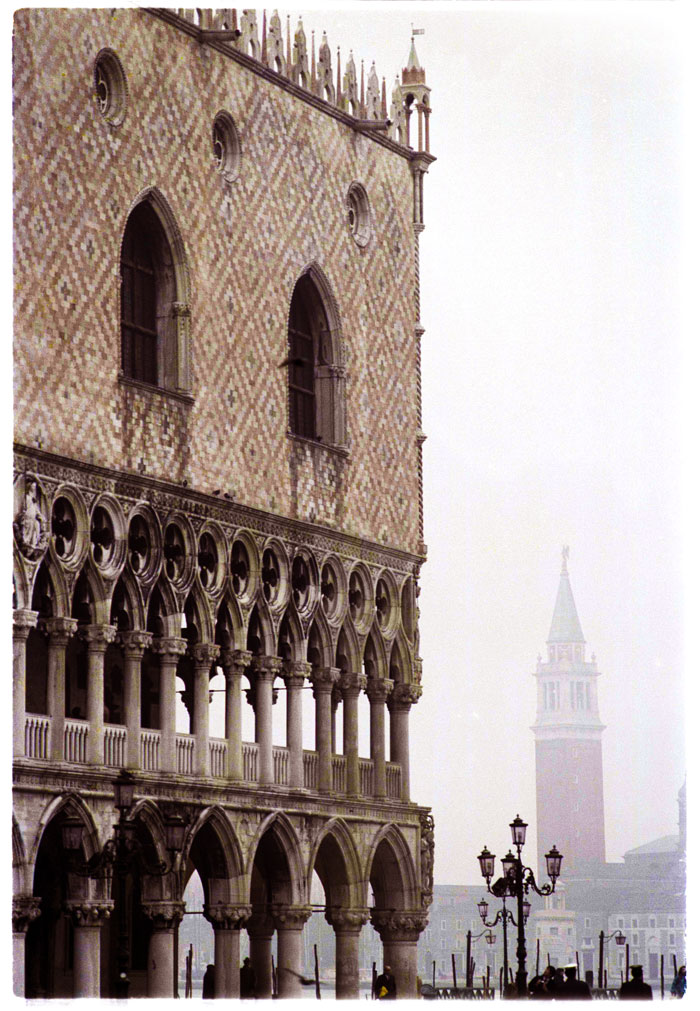

This is a photo I took of the Holy Steps to the Basilica of Santa Maria in Aracoeli and Michaelangelo's stairs to his piazza on the Capitoline Hill. (Michaelangelo to the right.)

When the pandemic hit in 2020 we'd only been in our South Bronx loft for a few months. We threw a housewarming party, in fact, on February 29—Leap Day. We'd just heard of the virus being detected in New Rochelle a few days before and wondered if we should go ahead with our plans; a week later New York was shut down. It was the last (and best) party of the year.

Except for all my classes going online the pandemic had minimal impact on my day-to-day. I hated having the theaters shut down; I wore a mask when I went to the deli or got on the subway. C took over the grocery shopping as I was seen as high-risk; later we signed up for Fresh Direct and had all groceries delivered. I did love deserted New York; walking through Times Square minus people was like a scene from a science-fiction movie. I always had a soft spot for the global apocalypse genre.

I started a couple of large projects since there wasn't much else to do. The loft had a lot of room and it was really comfortable working on stuff that would have been much more disruptive in a smaller place. The first project was going deep into the archives and scanning (or rescanning, depending on condition) every negative or slide I'd taken between 1972 and 2004. Those were the years I was shooting with film. (I got a decent camera in '72, a used Honeywell-Pentax.) There were thousands of images and many had been stored poorly.

That project was the genesis for this website. I scanned and eveluated about fifty-thousand images, and tried to arrange them in chronological order. I thought it might tell me something about my life.

As I mentioned a huge percentage of these pictures had been poorly stored; temperature and humidity can wreak havoc on an emulsion. I usually developed the monochrome negs myself and my darkroom techniqes caused many of the original issues. Nothing had ever been handled with the cotton gloves the professionals use. After the darkroom work they'd been jammed into envelopes with no separation betweem the four, five, or six-image strips. Sometimes they'd been stored in cheap plastic holders that broke down over time and adhered to the negatives. Sometimes they looked as though they'd been spread out on a basement floor for a couple years. Every square centimeter reveled minute cracks, splotches, or white scratches dug deeply into the plastic.

Photoshop makes very good judgements about what the original color of the image might have been; I typically make a pass with its Auto Toning, Auto Contrast, and Auto Color menu items. Auto Color can make a signicant correction that is difficult to duplicate with other tools. My favorite filter at the moment is the Camera Raw; this is particularly good at restoring details in shadow areas and can make the image appear sharper with its Clarity slider. Sometimes I enhance contrast here or add some saturation or some edge sharpening. All these things have to be used with a light touch. I always start here because this step makes the flaws in the image more apparent, and therefore easier to correct.

This is about a 200% blowup of the original, and we can clearly see the emulsion cracks that are in every part of the negative.

I used the Clone Stamp tool or the Healing Brush tool to eliminate every crack and every white spot. I've always called it spotting; Adobe probably has a better name for it. This is the most tedious part of the process; a negative this damaged can take twenty or thirty hours. Every time you use the tool you're making a choice: is this a flaw or is it a detail? Will the Healing Brush soften the focus, or should I use the Clone Stamp instead, grabbing texture from a similar area? I'm typically working at a 300% blowup where image components are quite abstract; not quite at the pixel-editing level but not far off. The judgements have to be based on doing this many times with many other images. When you do it wrong you create areas that are far too smooth; all the detail has been sandpapered away. Doing it right preserves the detail but creates a creaminess that is very satisfying. It's hard to describe.

And now we come to the part that is the most philosophically challenging. Do we have an obligation to present the world as it is, or as we want it to be? Do we have the right to change reality to make our compositions more interesting? Are we taking something away from our pictures by attempting to make them perfect? I know some photographers are ruled by a compelling ethic: this is what I saw through my lens. This dictates all sorts of things in their editing process, down to including the raw edges of the original negative in the print. (Fortunately for liars like me, these ragged negative edges are easy to fake!) The New York Times is very strict about this stuff; they've fired people for darkening clouds of smoke over an explosion.

I don't feel like I have to adhere to the realism of the Times, but even as I'm making huge changes to a photo I'm pondering the morality of what I'm doing. That's how it feels to me, like a moral issue. Maybe that's because I was raised as a Catholic and look for guilt in the most obscure places. Maybe I'm troubled by the digital makeover of the world and feel like I'm part of some problem. Maybe I just think (at least sometimes) that these modifications can't possibly be as interesting as the real world. As always, I have no idea why I do what I end up doing. (What exactly is the real world, anyway?)

On the right of the image, adjacent to Michaelangelo's steps leading up to the Capitoline plaza, there is a barrier with a red-and-white caution sign attached. I decided I wanted it and some adjoining signage out of my picture. Mostly by painting with the Clone Stamp tool I have eliminated the barrier and the signs. For some reason it caught on the edge of my eye like a bad edit does when I'm working on a video. I can't explain it; for some undefinable reason it seems like the image would be better with those details gone. I could also be wrong. I agonize for a while and sometimes reverse myself. Again I'd like to emphasize that I have no idea what I'm doing.

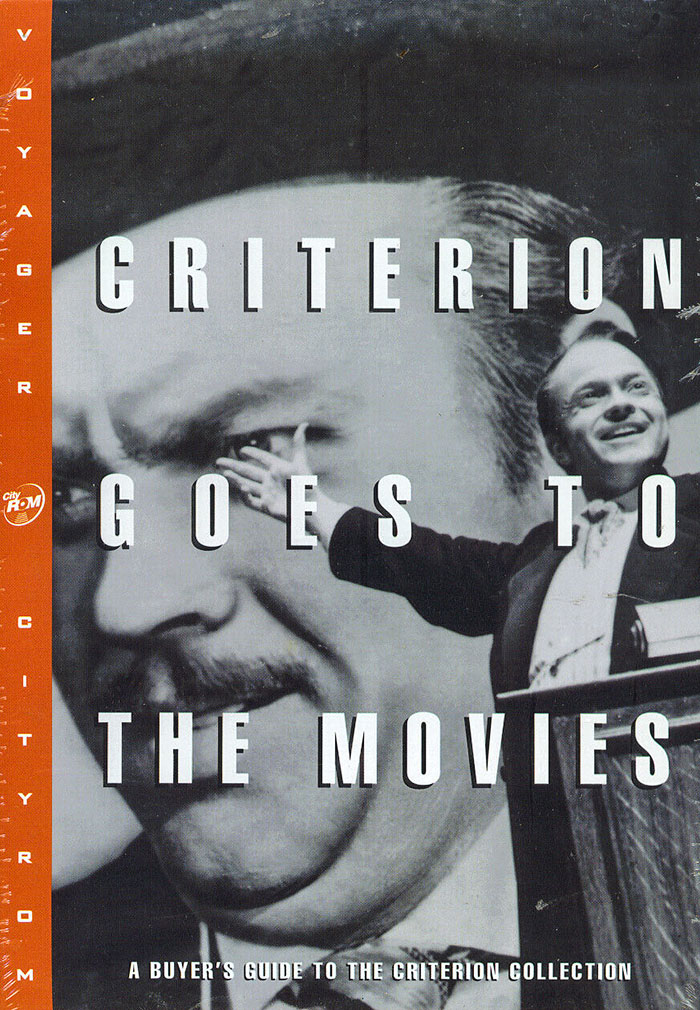

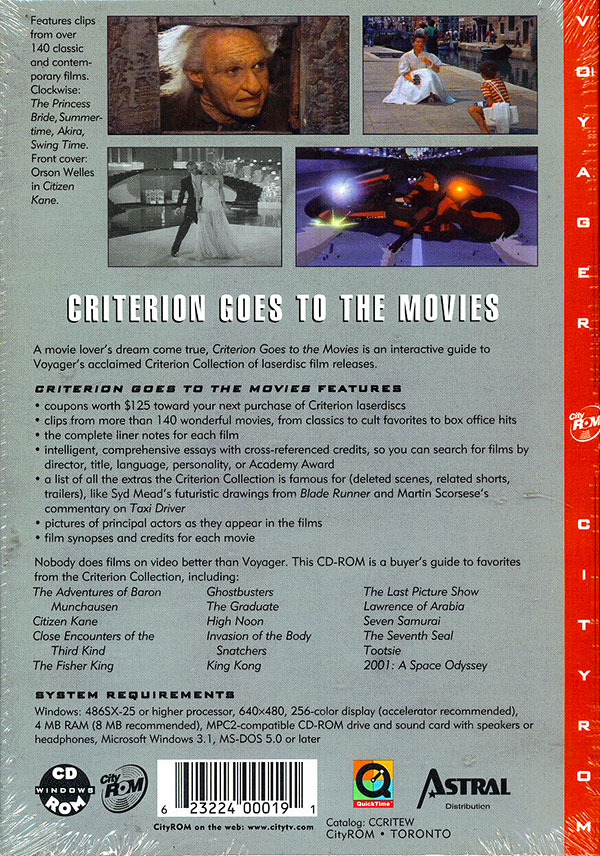

Before I even had time to graduate from the Interactive Telecommunications Program, I was in business with with my friend Janet, a fellow student and the best designer I've ever met. We called ourselves Bedrock Design. Our first project, a CD-ROM for The Voyager Company called Criterion Goes to the Movies, was derived from our thesis project. It was an interactive, multimedia guide to the Criterion collection of laser disks.

Back in my apartment I had a copy of a huge New York Times library reference book that was a sort of almanac of movie history. Among other items, there were all the reviews the paper had ever published, chronologically arranged. This section was followed by a compendium of film actors, each actor seen with credits and a picture. In the early 90s this was fantastic, a resource like no other, and exactly the type of endeavor the web has completely replaced. My shelves of movie books (still so precious to me!) date me as a veteran of pre-Internet information scarcity.

Janet and I had come up with the idea of a digital encyclopedia of film that would provide a useful and intuitive interface to gobs of movie info. I wanted to do something like what the Times had done with their almanac. Somehow we were in touch with Bob Stein of Voyager just as the company was putting together some of the very first CD-ROMs, discs that offered a new kind of experience with art and/or music. Voyager finally ended up calling them Expanded Books; they are studied now by scholars researching the evolution of tech. Laurie Anderson made one; The Residents made one; denizens of the 80s East Village art scene experimented with the concept. At ITP we thought this was the future, and in a way we were right. We just made a small mistake as to how the work would be delivered.

Voyager was in partnership with Criterion, which was

in turn an offshoot of Janus Films, the famous distributor of hundreds of European, Asian, and US indie art films. It's the same Criterion that is ubiquitous in today's market with hundreds of Blu-rays and a streaming channel. The

Criterion collection all started with Janus.

Voyager was in partnership with Criterion, which was

in turn an offshoot of Janus Films, the famous distributor of hundreds of European, Asian, and US indie art films. It's the same Criterion that is ubiquitous in today's market with hundreds of Blu-rays and a streaming channel. The

Criterion collection all started with Janus.

During the 1980s a significant part of the collection was issued on laser disc. Laser discs hit the market about the same time as VHS and Beta tape devices but never enjoyed the same market share; only two percent of households in the US ever had one. You could not record on a laser disc. It was the last flourishing of analog home video, far better than the tapes but still not entirely digital. It was a short-lived technology but state-of-the-art for film collectors. DVDs ended the whole concept of the laser disc by 2001.

Thus came about the merging of our thesis concept with the Criterion laser disc collection. There would be an essay on each film, complete credits, an actual clip from the movie, and screen-captured photos of every person mentioned in the credited cast. All this arranged in an intuitive interface, and best of all, it was interactive! It was multimedia! Everything back in those days shouted interactivity and multimedia; hardly anyone knew what you meant. The concepts are so thoroughly ingrained in today’s web experience that it doesn’t need explaining.

The disc was programmed (by me) in the HyperCard authoring environment, eventually given away by Apple with the first Mac computers; they called it programming for poets.

You didn’t

need to know machine code; the language was very much like English. The environment was easy to understand and navigate; the organizational metaphor was a stack of cards, each containing some information or graphics or both. Extensions

were written by third-parties that enabled the stacks

to control attached hardware and early Quicktime videos.

Our video segments, captured in one of the first versions of the Quicktime format, were about the size of a postage stamp. They were not high-definition; they had very low frame rates and very low resolution. They weren’t even stereo. We had to buy special equipment to interface with the laser disc player. All this was tremendously exciting—it was digital video, with all the control and features that implied (especially if you had a vivid imagination).

It’s important to note that no one I worked with envisioned this technology would be available on the web. We barely knew what the web was, in fact, and we were studying new technologies. When I was preparing Best of Breed: The American Kennel Club’s Multimedia Guide to Dogs, I remember bragging about the extensive amount of footage contained on the CD-ROM. “They’ll never have video on the Internet,” I said.

Getting the screen-captures of all those credited faces turned out to be the most time-consuming part of the job. Eventually we had to hire a couple of students to work with the two laser disc players and just capture and edit faces. And then there was the visionary Mr. Stein; please goddess, save me from visionaries. I've worked for two of them. Unfortunately our contract never stipulated a limit to how many times we would redesign the interface. After our experience with Voyager that provision was on top of the list with all subsequent clients.

Janet and I did another CD-ROM called America Remembered: Views You Can Use, a royalty-free collection of Americana postcards. The young client was rich and unreasonable and impossible to please; the CD-ROM became another tedious and troubled work experience.

Finally Janet abandoned freelance life to become art director at MacMillan Digital USA, a new company created to convert MacMillan print properties to mass-market reference CDs. She was instrumental in getting me a producer's job with the same outfit. We both worked there for the next four or five years and witnessed at close hand the collapse of the CD-ROM business. I was the last employee.